| (1.1) |

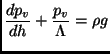

In 1895 H. A. Janssen [118] discovered that in a vertical cylinder the pressure measured at the bottom does not depend upon the height of the filling, i.e. it does not follow the Stevin law which is valid for Newtonian fluids at rest [137]:

where ![]() is the vertical pressure,

is the vertical pressure, ![]() the density of the fluid,

the density of the fluid, ![]() the

gravity acceleration and

the

gravity acceleration and ![]() the height of the column of fluid above

the level of measurement. The pressure in the granular material

follows instead a different law, which accounts for saturation:

the height of the column of fluid above

the level of measurement. The pressure in the granular material

follows instead a different law, which accounts for saturation:

where ![]() is of the order of the radius

is of the order of the radius ![]() of the

cylinder. This guarantees the flow rate in a hourglass to be

constant. Moreover, this law is very important in the framework of

silos building, as the difference between ordinary hydrostatic and

granular hydrostatic is mainly due to the presence of anomalous side

pressure, i.e. force exerted against the walls of the cylinder. It

happens that the use of a fluid-like estimate of the horizontal and

vertical pressure leads to an underestimating of the side pressure

and, consequently, to unexpected (and dramatic) explosions of

silos [128].

of the

cylinder. This guarantees the flow rate in a hourglass to be

constant. Moreover, this law is very important in the framework of

silos building, as the difference between ordinary hydrostatic and

granular hydrostatic is mainly due to the presence of anomalous side

pressure, i.e. force exerted against the walls of the cylinder. It

happens that the use of a fluid-like estimate of the horizontal and

vertical pressure leads to an underestimating of the side pressure

and, consequently, to unexpected (and dramatic) explosions of

silos [128].

The first interpretation of the law has been given by Janssen in his paper, in terms of a simplified model with the following assumptions:

In particular the first assumption is not true (the pressure depends also upon the distance from the central axis of the cylinder) but is not essential in this model (as it is formulated as a one-dimensional problem), while the second assumption should be obtained by means of constitutive relations, i.e. it requires a microscopic justification.

Imposing the mechanical equilibrium of a disk of granular material of

height ![]() and radius

and radius ![]() (the radius of the container) the following

equation is obtained:

(the radius of the container) the following

equation is obtained:

which becomes:

|

(1.4) |

where

![]() . This equation is exactly solved by

the function (1.2).

. This equation is exactly solved by

the function (1.2).

The particular behavior of the vertical pressure in granular materials is mainly due to the anomalies in the stress propagation. The configuration of the grains in the container is random and the weight can be sustained in many different ways: every grain discharges its load to other grains underlying it or at its sides, creating big arches and therefore propagating the stress in unexpected directions. Moreover, arching is not only a source of randomness, but also of strong fluctuations, i.e. disorder: in a granular assembly some force chains can be very long and span the size of the entire system, posing doubts on the validity of (local) mean field modeling.

Further interesting phenomena have been experimentally observed in the statics of granular materials:

Different models have been proposed and debated in the last years, in order to understand the problem of the distribution of forces in a silo or in a granular heap.

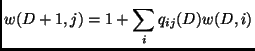

The q-model has been introduced in 1995 (remarkably a century

after the work of Janssen) by Liu et al. [141,66] in

order to reproduce the stress probability distribution observed in

experiments. The model consists of a regular lattice of sites each

with a particle of mass unity. Each site ![]() in layer

in layer ![]() is connected

to exactly

is connected

to exactly ![]() sites

sites ![]() in layer

in layer ![]() . Only the vertical components

of the forces

. Only the vertical components

of the forces

![]() are considered explicitly: a random

fraction

are considered explicitly: a random

fraction ![]() of the total weight supported by particle

of the total weight supported by particle ![]() in

layer

in

layer ![]() is transmitted to particle

is transmitted to particle ![]() in layer

in layer ![]() . Thus the

weight supported by the particle in layer D at the

. Thus the

weight supported by the particle in layer D at the ![]() -th site,

-th site,

![]() , satisfies a stochastic equation:

, satisfies a stochastic equation:

|

(1.5) |

The random variables ![]() are taken independent except for the constraint

are taken independent except for the constraint

|

(1.6) |

which enforces the condition of force balance on each particle. Given

a distribution of ![]() 's, it can be obtained the probability

distribution

's, it can be obtained the probability

distribution ![]() of finding a site that bears a weight

of finding a site that bears a weight ![]() on

layer

on

layer ![]() . By means of mean field calculations, exact calculations and

numerical solutions, the authors conclude that (apart of some limiting

cases) a generic continuous distributions of

. By means of mean field calculations, exact calculations and

numerical solutions, the authors conclude that (apart of some limiting

cases) a generic continuous distributions of ![]() 's lead to a

distribution of weights that, normalized to the mean, is independent

of depth at large

's lead to a

distribution of weights that, normalized to the mean, is independent

of depth at large ![]() and which decays exponentially at large

weights. They find also a good agreement with molecular dynamics

simulations of the packing of hard spheres. The q-model has many limits:

and which decays exponentially at large

weights. They find also a good agreement with molecular dynamics

simulations of the packing of hard spheres. The q-model has many limits:

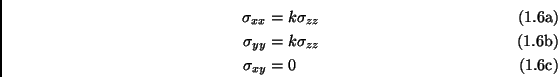

A more refined version of the Janssen model has been introduced by Bouchaud et al. [36]: the authors have considered a local version of the Janssen assumption on the proportionality between horizontal and vertical stresses:

|

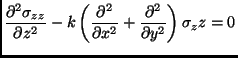

which lead to the linear equation:

|

(1.8) |

This equation for the vertical stress is hyperbolic and therefore

differs from the equivalent equation for an elastic medium, which is

elliptic [136], and from the q-model equation that is

parabolic (as a diffusion equation): it is equivalent to the equation

for the wave propagation with ![]() as the ``time'' variable and

as the ``time'' variable and ![]() as

the inverse of the propagation velocity. This model well reproduces

the dip in the measure of the pressure under the bottom of the conical

heap [217]. A cellular automaton was introduced by

Hemmingsson [106] which was capable of reproduce the

dip under the heap as well as the correct Janssen law (with the linear

scaling).

as

the inverse of the propagation velocity. This model well reproduces

the dip in the measure of the pressure under the bottom of the conical

heap [217]. A cellular automaton was introduced by

Hemmingsson [106] which was capable of reproduce the

dip under the heap as well as the correct Janssen law (with the linear

scaling).

In the framework of the study of force networks in the bulk of a

static arrangement of grains a key role was played by the experiments

on the propagation of sound. The inhomogeneities present inside

a granular medium can drastically change the propagation of mechanical

perturbations. Liu and Nagel [139,140,138] have addressed

this issue in several experiments. They have discovered [139]

that the in the bulk of a granular medium perturbed by a harmonic

force (![]() Hz) the fluctuations could be very large, measuring

power-law spectra of the kind

Hz) the fluctuations could be very large, measuring

power-law spectra of the kind

![]() with

with

![]() . Then they have seen [140] that the sound group velocity

can reach

. Then they have seen [140] that the sound group velocity

can reach ![]() times the phase velocity and that a change in the

amplitude of vibration can result in a hysteretic behavior (due to a

rearrangement of force chains). They have also measured [138] a

times the phase velocity and that a change in the

amplitude of vibration can result in a hysteretic behavior (due to a

rearrangement of force chains). They have also measured [138] a

![]() variation of the sound transmission as a consequence of a very

small (compared to the size of the grains) thermal expansion of a

little carbon resistor substituted to a grain of the granular

medium. This sensitivity to perturbation is another signature of the

strong disorder (arching and chain forces) in the bulk of the medium.

variation of the sound transmission as a consequence of a very

small (compared to the size of the grains) thermal expansion of a

little carbon resistor substituted to a grain of the granular

medium. This sensitivity to perturbation is another signature of the

strong disorder (arching and chain forces) in the bulk of the medium.